A Senegalese painter puts his memories under glass

By Christina Barbin

By that time, Gora Bengué was no longer an unknown artist. His paint- ings had already begun to interest collectors not only in his own country but also in other African countries such as Ivory Coast and Mali; and he had already had several exhibitions in France. When he recently showed his work at Unesco's Paris headquarters, Gora M'Bengué demonstrated the very unusual technique by which the artist paints on the back of a piece of glass, reversing the normal order of composition (beginning with the highlights and ending with the background); the completed painting is viewed from the front, through the glass.

This technique lends the colours used, which are generally bright, a special luminosity that is not affected by the passage of time. Painting under glass was first carried out towards the end of antiquity; but the fragility of the medium has meant that almost no examples of such paintings have survived from then or from the Middle Ages. The technique is used in the Arab countries and became widespread in India from the 18th century on (the East India company distributed some highly refined examples). In the 17th century, European Jesuits introduced the technique in China, where paint- ings were executed with a skill that has never been surpassed.

In Europe, the genre reached its apogee in the 19th century, particularly in the field of folk art. Until the middle of the 18th century, the technique was essentially used in sophisticated works and restricted to cities. But from then on it became integrated into popular tradition and was given a new lease of life in rural areas, where glass was already commonly used. The technique spread from the important glass- making centres of Murano and Bohemia to the rest of Europe. In Sicily, Romania, Alsace and the Rhineland, Switzerland, Austria, Slovakia, Moravia and Silesia, Spain and Portugal (two countries which exported the technique to Latin America: glass votive offerings are to be found in Mexico and Brazil), many anonymous artists gave a deliberately naive and almost exclusively religious character to the art, which qualified for the description "baroque", pro- vided that the adjective is understood to mean something basically of a popular and rural nature as opposed to classical, academic art.

The technique of painting under glass was widely used during the 1950s in Senegal, when Gora M'Bengué, who had been drawing on paper since childhood, decided to adopt it. Its luminosity suits his vision of the world, which has retained something of the wide-eyed wonderment of the child.

Bengué is an incarnation of popular tradition. He is a self-taught man (his father was a farmer) for whom paint- ing is a vocation that brings him closer to the land. "One has to like one's job to do it properly", he says. "I used to work in the fields with my father and draw at the same time, until the day when first drawing, then painting became a permanent need for me. But that doesn't mean I've abandoned the land: I paint landscapes and scenes of rural life".

Like many "naive" painters, Bengué spreads his paint in broad, strongly coloured flat strokes, tends not to highlight shadows, and uses almost no perspective. He does no preliminary sketches. "I do freehand drawings, following the inspiration of the moment, which in fact comes from deep down in my memories. The minute I start drawing I know exactly what I want to do: my hand dictates the line. I just need pens, Indian ink, paint and brushes. I don't draw from the model, I use my imagination. I'm quite incapable of drawing the same thing twice - each painting is unique. I often work at night, locked up in my room”.

Bengue's refreshingly naive paint- ings are nonetheless a riot of colour. As in 19th-century paintings under glass, the deliberate lack of formal realism in no way detracts from the content's documentary value. His work depicts scenes of everyday life in Senegal more than 50 years ago - women wearing traditional costume and hairstyles, farm workers, hunters, traders, a whole world that has since disappeared. "I like painting the past because it's a way of preserving it".

This is a tendency, or rather a profound need, observable in all artists, including those who express themselves in completely different forms. After all, it was Jorge Luis Borges who said: "I write for myself, for my friends, as well as to stop the march of time".

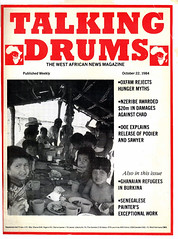

Gora M'Bengué demonstrates his painting technique at Unesco's headquarters. One of his favourite occupations is to pass on the secret of his technique to children. Unesco photo by Michel Claude.