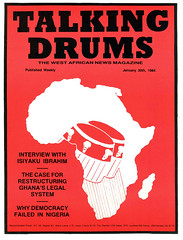

American-Style Democracy In Nigeria - A Failed Experiment?

Emmanuel A. Annor, Los Angeles

Whichever way you look at it, little purpose will be served if we wring our hands and bemoan the demise of democracy in Africa. Rather, the change should be considered as a challenge and an opportunity: a challenge not to give up the experiment with democracy, and an opportunity to re- examine critically the basic ingredients that are essential for democracy to take root in Africa.

Nigeria's adoption of American style democracy from the constitution to the expansion in the institutions of higher education was almost total. Unfortunately, the adoption of American institutional forms came without the adoption papers. The social infrastructure had not gone through the same evolutionary process as had that of the United States. It was, therefore, not surprising that by the end of the first term of the democratic experiment, many cracks had appeared at the seams.

True, Nigeria had a vibrant and free press: the freest in Africa. Indeed, if the present military junta picked on corruption among public officials as the prime motivation for the intervention, it was mainly because of the wide press coverage of such excesses. But unlike the journalistic coups which often occur in America (the most dramatic of which resulted in the resignation of President Nixon), the Shagari administration appeared to have made the concept of freedom of the press meaningless. Not only was it helpless in the face of public outcry against the blanket plundering of the country's resources, it did nothing to bring known culprits to justice.

This apparent insensitivity to press criticisms aside, the brazenly manner in which the nouveaux riches carried themselves about in public view (a recent craze was to own private jets!), in a society where changes in personal fortunes become easily noticeable, seriously undermined public confidence in elected officials.

And as if to mimic the era of the land-grant colleges of the United States in the nineteenth century, institutions of higher education proliferated in Nigeria. But again, unlike the land- grant colleges these new institutions lacked clearly defined goals. When oil revenues started to dwindle, a heavy strain was put on both state and federal government resources.

DICTATORSHIP

These are but a few of the institutional forms which appeared to have worked in the United States, but which apparently made less than significant impact in Nigeria.Nigeria's case then is that of a painful irony of wealth. The oil boom enabled her to purchase whatever was available on the world market for rapid modernization, but apparently she lacked the infrastructure to absorb all the new products with their imported values!

This is, of course, not to argue that the military can provide any credible solution to the hydra-headed problems of that country. If anything, past military dictatorships have tended to be more corrupt and incompetent than the civilians they overthrow. And wasn't the current wave of corruption started by the military which ruled for thirteen years in Nigeria?

Nevertheless, the New Year's Eve coup should awaken Nigerian intellectuals and those interested in democracy in Nigeria to evaluate the fundamental issues which underlie so much of the political instability in that region. A critical question is the role of the military in national development. Clearly, no definitive role had been carved for Nigeria's well-armed, 250,000-strong army. A much larger question, of course, is how rapid modernization can take place in an environment of motley traditional forms and foreign influences.

Rather than lamenting the demise of democracy in Nigeria, the optimist can take consolation in the fact that it took numerous wars, court intrigues, decapitations, and for sure, coups d'etat, before Western Democracies evolved to their present shape and form. Perhaps what happened in Nigeria is part of the teething pains in the evolutionary process, and painful as the process may be, the experiment should never cease. What Nigerians probably expect from western observers at this point in their history is neither sympathy nor an attitude of I-told-you-so, but an appreciation of the inevitable growing pains which experience alone can teach. Viewed this way, we can still look to the future with hope.