The Military - Servants Or Masters? (2)

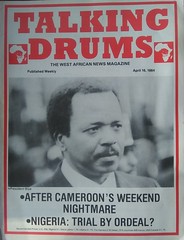

Colonel Annor Odjidja

"Once an armed force is politicised it is only a matter of time before the fabric of professionalism that exists in military organisation is destroyed, with disastrous consequences for the nation it is sworn to serve". by Col. Annor Odjidja Who was identified in the first instalment of this article published last week as Tetteh Hedzi. He was the Director of Military Intelligence in the Ghana Armed Forces until the coup of 31st December 1981.The 1972-79 interregnum reversed all the attempts at reform. The freeze on recruitment and expansion of the Armed Forces was lifted. This decision resulted in the intake of considerable numbers of officers and men of doubtful calibre and quality, and of distinctive political beliefs. The groundwork for the 1979 and 1981 coups was laid down by this decision. No serious effort was even made during this period to provide a lasting solution to the problem of the employment and size of our Armed Forces.

The next attempt at reform took place under the Limann administration. This government set up the Coussey Commission to review the roles, size and structure of our armed forces. By the time the commission completed its work, the Limann administration had been overthrown. It remains to be seen whether this military government will ever implement the recommendations of the commission. On past form, it is most unlikely to expect the PNDC to do anything about the armed forces.

It is evident that no serious attempt has ever been made to determine the operational uses to which our armed forces can be put. It is also clear that the size of the Ghana Armed Forces has no relevance to any identified operational needs. What we have today has grown from the relatively small colonial force without any rhyme or reason. The consequence of this is that our Armed Forces consumes a proportionately larger share of a declining resource, since it has remained virtually the same size and in view of the negative growth of our economy over the years, it is tempted to intervene in politics, because it does not know what it has been established for. Major-General Paley, a former commander of the Ghana Armed Forces, once warned that politics must be kept out of the Armed Forces and the Armed Forces must stay out of politics. The essence of his warning is that if politics is introduced into an armed force it becomes politicised. Once an armed force is politicised it is only a matter of time before the fabric of professionalism that exists in a military organisation is destroyed, with disastrous consequences for the nation it is sworn to serve.

The Ghana Armed Forces has, since 1958, become so politicised that today our men in uniform have lost all claims to the competence and neutrality that is at the basis of a standing professional force. The genesis of this politicisation began in the 1950s/1960s when the CPP/UP dichotomy found a sympathetic chord among the officer corps. For the Nkrumah regime, the presence of officers who shared its political views and were prepared to support it politically, was most welcome.

They were therefore given key command and staff responsibilities, whether they showed any competence or not. For the UP which wanted Nkrumah out of the way and rejected his political ideas, the task was to find sympathetic officers who were prepar ed to assist in the overthrow of the Nkrumah regime and the end of what they perceived as dictatorship. The polarisation which the CPP/UP political conflict caused among the officer education of the officers of the armed forces only served in the end to height- en the political consciousness of our officers. They were opposed to what they termed "communist indoctrina- tion". His political opponents used this to intensify their infiltration of the officer corps with their own political message. This was to contribute to the increasing politicisation of the officer corps, to the extent that today the officer corps is divided into pro and anti-CPP. If you accept that successor parties in Ghana drew their inspiration from the CPP/UP dichotomy, then the influence of the continuing debate between the two main strands of polit- ical opinion in Ghana on the officer corps can be gauged.

The institutional framework for internal security operations in Ghana also contributed to the politicisation of our Armed Forces. Our men in uni- form have always been involved in the meetings and deliberations of internal security bodies in the country at all levels. The threats to internal peace that forms the bulk of discussions at these meetings have always had a major political content. Armed Forces representations at such meetings have had to be involved in discussions no professional soldier should be encour- aged to take part in without an overhaul of the national internal security organisation to make political repres- entation bipartisan and an agreed rationale for the use of troops in internal security operations, the political consciousness of officers will increase in time..

VENGEANCE

Until the withdrawal of military rep- resentatives from lower levels of the internal security organisation is effected, this source of politicisation will retain a potent influence on the political attitudes of the officer corps. The 1966 coup had the effect of bringing politics into our Armed Forces with a vengeance. Officers were sent in to administer government. For the most part, the political orientation of the soldier politicians drew its influence from the UP. The activities of the CPP was severely curtailed. The 1967 coup attempt by S. B. Arthur was seen as the CPP's revenge for being kept out after the overthrow of Nkrumah and aimed at the UP influence in the NLC.Any observer of the Armed Forces at that time would have been impressed by the pro-CPP sympathies of the junior officers and the other ranks, and the charges against the NLC - corruption, promotions of senior officers and the general incompetence of the magician to predict that these attitudes will gain strength in the future. 1967 was perhaps the harbinger of things to come! The handover by the NLC has been acclaimed as a classic example of gentlemen officers agreeing to do the proper thing and bring in the politic- ians. It was no such thing. The NLC was forced to hand over because it was split and more because there was the likelihood of another coup before 1970 if it continued to stay in office.

A problem for stability during the years of the Busia government was the continued disenfranchisement of the CPP. It was evident that they did not accept this and were looking for ways to have this reversed at the least oppor- tunity. The implications of this situa- tion was a source of security concern to the Busia government.

A more important problem was the position of the Ghana Armed Forces in the civilian era. The dilemma facing our armed forces after 1969 was how it could be persuaded to revert to its trad- itional roles, whatever they meant in the Ghana context, under a civilian leadership now that it has tasted power.

The disenfranchisement of the CPP was one of the factors behind the return of the military to government in 1972. The 1972-1979 military government provided a wider scope for milit- ary participation at all levels of government. For the first time, discussion of political issues was institutionalized in the Ghana Armed Forces through the Military Advisory Council, a representative body of senior commanders and staff officers of our Armed Forces. It was the Parliament of the Supreme Military Council. Its influence could be gauged by the major role it played in the removal of Acheampong from office.

The long period of military rule created deep dissatisfaction within the Armed Forces. Junior officers and other ranks became incensed at the way the benefits of soldier government accrued to the senior officers and their acolytes. A study of all the attempted coups during this period will reveal that it was made up of junior officers and other ranks who felt that they should be given the opportunity to govern the country. They claimed the deterioration of the economy as their main reason for action but the underly- ing factor for these attempts was the desire of the young officers and other ranks to have a piece of the action. Having seen the benefits that power brought to their senior colleagues in government, they also thought that their time had come. As the date for the return to constitutional rule approached, they realised that they had to take action immediately or they themselves. It has been said that the 4th June action was primarily a move to end the military's role in government and end military corruption.

It was more a move to replace one group of soldiers in government with another. The ideological cloth that was wrapped around the AFRC was more of an afterthought, designed to justify the 4th June action. But it had the effect of politicising the other ranks. The 4th June action made Rawlings a symbol of other rank politics and their ambitions for power.

Once the AFRC handed over power to a civilian government, it was safe to assume that the return of Rawlings was only a matter of time. The hunger for power and the benefits which this brought had been only partly satisfied during the short period of AFRC rule. Other rank appetite for a return to the days of the AFRC when they had real power, could only increase in time between 1979 and 1981. It needed the naivety and the seeming weakness of the Limann government for Rawlings and the other ranks to force another change of government. From December 1981, power was once more in the hands of the armed forces but this time other ranks dictated the pace. Military intervention in our politics had started at the top of our Armed Forces but through a series of coups and attempted coups, it had reached the proletariats of our Armed Forces.

ATTITUDES

At the basis of the military's predilection for intervention in politics lies attitudes of mind which provide stimuli for coups. Our men in uniform have a contempt for the civilian and all he stands for. They think he is lazy, inefficient and incapable of taking firm decisions. Our soldiers believe, strang ely enough, that Ghanaians are not disciplined. Never mind that the worst cases of indiscipline have always been recorded in the Ghana Armed Forces.An important ingredient in the attitudes of our men in uniform is the belief that they have better skills and brains for dealing with problems of the country. Yet they are deeply suspicious of thinkers. The worst condemnation a Ghanaian soldier could give anyone is to call the fellow 'book-long'. This anti-intellectualism is at the basis of their opposition to all reform in the Ghana Armed Forces.

They tend to be impatient with constitutional processes and are ready, at a given opportunity, to replace these with their own perceptions of government. They feel that the civilian is basically anti-military and is looking for any opportunity to disband the Armed Forces. Thus when outsiders are suggesting changes to the Armed Forces or assist in reforms, they are most likely to react negatively, believing that they know best and can do these best. It should be understood that despite the divisions that have appeared between officers and other ranks, these attitudes are held by all ranks, the other ranks perhaps being more crude in giving expressions to these attitudes.

The Ghanaian politicians' perceptions of the soldier are interesting for the change it has undergone since 1979. Between 1966 and 1979, he felt that the Armed Forces was the final arbiter in the contest between the two main political parties in Ghana. His contention then was that the armed forces was the power of last resort, to be called in when all avenues for affecting change had been exhausted. This was the argument he used in 1966, 1972 and 1978. But as the realities of other rank rule in 1979 and the prospect of a repeat after 1979 dawned on him, this attitude was replaced by one of impatience with soldiers in government. Hence a radical change in his perception of the ability of our men in uniform to govern the country.

After the handover to the Limann government, all the politicians were united in their determination to preserve civilian rule, even though a considerable number of them continued to maintain links with the Rawlings movement waiting in the wings. They were the group that provided Rawlings with the support and advice to seize power and have joined his administration.

After October 1979, the Ghanaian politician was very suspicious of our men in uniform. In his perception, the soldier represented a brutal, uneducat- ed group, ready to subvert the new democratic experiment and not under- standing the complex nature of civilian government.

The Limann administration missed a wonderful opportunity after 1979 to take advantage of this attitude to encourage the political parties to develop a common political action programme against military intervention in the Third Republic. There were powerful political figures within his own party which opposed dialogue with the minority parties on this issue. This lack of unity facilitated the return of Rawlings. In the end the ruling party took the line of least resistance. This was to regard the problem of military intervention in purely party terms. Hence the emphasis on placing pro- PNP officers and personal favourites in key command and staff positions. They worsened the situation further by recruiting their own sympathisers among other ranks.

As an anti-coup measure, it was bound to fail because experience of the past has shown us that when a coup takes place, all these acolytes always disappear and later to throw in their lot with the coup makers. A classic example of military solidarity!

This dichotomy in the military politician relationship is one of the factors for military intervention in politics. The soldiers' apparent refusal to understand the need for the development of strong and mature civil institutions and his contempt for the democratic process are the reasons why no civilian administration since 1969 has survived its full term. The sense of superiority that our men in uniform feel about themselves is one of the factors that has encouraged their intervention.

It needs to be noted that one of the reasons why our soldiers have intervened in politics is that the cost of insurrection to the coupmaker is not high. Officers and other ranks who have attempted coups have always been dealt with rather leniently. When a successful coup occurs, they are often released from jail, after serving only a small part of their sentences. The cost of failure to the coupmaker is often not high enough to deter him. If he failed in his attempt, he could expect to get a light sentence and hope that within two years his successful military colleagues will free him. On the other hand the benefits of success are very high.