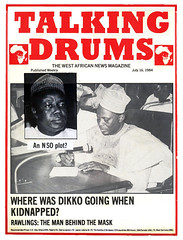

The Price To Pay Under Decree No 4

- 11 Foreign Missions to be closed down (March 31)

- Eight military chiefs tipped as Ambassadors (April 1)

- Haruna replaces Hannaniya U.K. envoy (April 8).

They were, however, convicted on the third count and the two journalists were jailed for one year each and the Guardian fined N50,000. The minimum fine allowed under Decree 4 is N10,000.

Before the sentence was passed, a mitigation plea was made by Mr Ladi Williams, whose father Chief Rotimi Williams defended the journalists. The bases of his plea were that Mr Thompson and Mr Irabor had been detained since April, that they were first offenders who by the account of their character by witnesses had performed their duties honestly and objectively.

Although ignorance of the law was no excuse, Decree 4 was promulgated so close to their arrest that they would not have found the time to study it exhaustively. That the two journalists had been freed on two of the three counts indicated that the prosecution had no case against them.

That Mr Thompson is married with three children the youngest of whom is seven months old.

Mr Irabor, a bachelor, was to be married on the first Saturday of October and that the Guardian newspaper was just one year old and its finances were still fragile.

Mr Ladi Williams consequently urged the tribunal to impose a one-day sentence which he said was still consistent with the Decree.

After a forty-nine minute recess the tribunal resumed to pass sentence. Mr Justice Ayinde who said he had taken into consideration all the points raised in the plea for mitigation then stated: "However, we shall be failing in our duty if we fail to impose sentence that will serve as a lesson and deterrence to other journalists who did not check the veracity of their reports before publications

On count three - Haruna replaces Hannaniya as new U.K. envoy - Mr Justice Ayinde disagreed with Chief Rotimi Williams, defending, who had said that Mr Thompson and Mr Irabor, could not be charged with publishing the statements because they were mere authors or writers.

Mr Justice Ayinde said: "Publication is accompanied in a variety of ways according to the subject matter. A book or other literary matter is published by being surrendered by its author for the public use. A newspaper or periodical is published whenever and wherever it is offered to the public by the proprietor (See Shroud's Judicial Dictionary 4th edition under publication's publish).

"I have said in this judgement that the offence of publishing false statement, report etc. under section (1)(i) of the Public Officers (Protection Against False Accusation) Decree 1984 is akin to the offence of publishing seditious publication contrary to section 51(i)(c) of the Criminal Code".

"The word 'publish' used in section 1(i) of the Decree will be interpreted in the same sense as it is used in seditious publication offences. In seditious publication offences, the word 'publish' is in variety of ways".

Citing several legal authorities, Mr Justice Ayinde said: "The editor, assistant editor and other officers directly concerned with the publishing of newspapers of a company may be charged and punished for publishing seditious writing".

He then said that with the reasons given and having regard to the authorities cited and examined, "it is our view that the word 'publish' used in the context of section (1)(i) of the decree should apply not only to the company publishing the newspaper, but also the officers of the company responsible for publishing articles in the newspaper and also individuals who submit articles for publication in this newspaper.

Mr Justice Ayinde added: "Furthermore, section 8(i) of the Decree prescribes imprisonment of not exceeding two years for any person found guilty of an offence under the Decree. This shows that it was the intention of the Federal Military Government which enacted the Decree that a human being apart from a corporation could commit the offence of publishing false statement, rumour, etc. contrary to section 1(i) of the Decree.

Chief Williams had argued that, under the laws of Lagos State where Guardian Newspapers Limited is based, the 'publisher' of a newspaper was distinct from its reporters or editors. In that case, he said, only the publisher could be accused of publishing wrong information.

To him, Mr Thompson and Mr Irabor could only be considered authors or writers of the "false publications" complained of. And in a description of newspaper process, Chief Williams explained that writers and authors had no power to get a newspaper to publish their works.

To counter claims by the prosecution that reporters (writers and authors) were liable because the decree allows for the punishment of officers whose ranks were "similar" to the editors, Chief Williams explored English grammar and authorities to show that a reporter did not hold a "similar" office to the "publisher's", and is not in a similar position as the editor.

But Mr Justice Ayinde, overruling, added: "To say the word 'publish' used in the context of sub-section (1) of section 1 of the Decree does not apply to the first (Thompson) and second accused (Irabor) persons is to defeat the intentions of the Federal Military Government in enacting the Decree and to render the said provision nugatory.

"In view of the foregoing and for the reasons already given, we find that the three accused published the statement 'Haruna replaces Hannaniya as new UK envoy', which was false in every material particular in the issue of the Guardian newspaper of 8 April, 1984. We also find the accused, since they did not give evidence, have failed to discharge the onus placed on them by section 1(i) of the decree.

"We, therefore, find each of the accused guilty of the offence in count three contrary to section 1 sub-section (i) of Decree No. 4 of 1984."