What The Papers Say

The Stalemate Over Aid

National Concord

Not entirely unexpectedly, the recent talks between the 64 African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries and the 10 European Economic Community (EEC) member-states ended in stalemate. Although officials of the two groupings tried to make the best out of a sad situation by sounding notes of optimism towards the future, the fact could be no means be played down that the talks had fallen regrettably short of unknotting the key financial question obstructing renewal of the five-year agreements for development Nigeria. assistance and trade preferences between both parties (generally referred to as Lome 11) which is due to expire next February.At the root of this stalemate is the disagreement within the ranks of EEC member-states on the level of their financial assistance to the ACP. While France had proposed a 50 per cent increase in the EEC aid package, if only to account for inflation and the rise of the dollar, Britain had objected arguing that the question of how much aid to provide its ACP partners be left exclusively to each individual EEC member-state to determine.

Furthermore, in response to the ACP request that the EEC tariff barriers to certain agricultural products be lifted, the EEC under pressure from Greece and Italy grudgingly agreed only to examine requests for reduced import duties on a case-by-case basis. And in response to another ACP plea for lower prices and improved credit conditions for purchases of surplus European agricultural products, the EEC states agreed to such favourable terms of trade, only within the limits of other existing international agreements.

The gloomy outcome of the negotiations and particularly the inflexibility (or insensitivity) displayed by the EEC states is largely reflective of official attitudes prevalent in the of the kidnapping. industrially-advanced nations, regarding the issue of development assistance to the Third World. Notable in Britain under Thatcher and the United States under Reagan, the marked resurgence of right-wing conservatism as much in economics as politics, has ensured a decline in aid to developing countries over the past few years.

This cheerless picture and its obvious implications for developing countries, strongly dictate that such countries now seriously consider long-term internal restructuring of their largely aid-dependent economies, and fresh initiatives in the campaign towards a new and fairer international economic order.

For one, such countries should now see to the prudent and judicious employment of whatever aid they receive, rather than pointlessly embarking on expensive white elephant projects which have little or no bearing to the betterment of their peoples' welfare.

Such nations, also, must mobilize a resistance against such pressure from donors, as would only further twist their economies to suit the designs of the industrial nations, thereby fostering the relationship of dependence. It hardly need be said, of course, that mustering such a resistance might well compel an in-depth reassessment of economic and political power relations within most developing countries.

This pursuit, quite clearly, is not the sort that developing break-through in any one of the issues involved invites the countries can undertake severally. The journey towards a collective and concerted participation of all Third World countries in a kind of south-south solidarity. And no countries are better placed to champion this cause than such "regional influentials" as India (in Asia), Saudi Arabia (in the Middle East), Mexico (in South America) and Nigeria (in Africa).

Send Them Packing!

Daily Mirror, London

Last week's attempt to kidnap a Nigerian politician and smuggle him back home in a crate was intolerable. We should say so whatever the cost in trade and friendship with Nigeria.In many ways it was worse than the outrage at the Libyan embassy in which a police-woman was murdered.

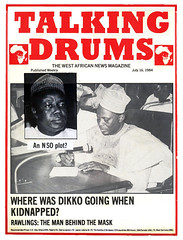

The snatching of Mr Umaru Dikko in a London street was not a lunatic act by a hothead. It was deliberate and premeditated and planned to the second.

And it was done knowing it broke every convention and practice of British and international law.

It was an act of contempt for our laws. It ridiculed the right of men to be presumed innocent before trial. The Foreign Office, wishing to preserve good relations with Nigeria, may pretend the kidnapping had nothing to do with the Nigerian Government.

We all know better.

After the Libyan episode, foreign governments may believe they can get away with anything in Britain.

That belief had better be ended straightaway.

If people seek refuge here, that refuge is not to be denied by any of the world's unscrupulous regimes. Mr Dikko may be a criminal under Nigerian law. But while he is in Britain, British law prevails.

The least we now require from the Nigerian High Commission is total co-operation in detecting the organisers

And if they're not prepared to give it, the sooner they are all sent packing the better.

Diplomatic Smash And Grab

The Times, London

In January 1981, when an attempt was made to transform the Libyan Embassy in Lagos into a "Peoples' Bureau", the Nigerian External Affairs Ministry promptly announced that the new arrangement was "totally unacceptable to Nigeria" and ordered the Libyans involved to leave the country. The decision was regarded at the time by diplomats in Lagos as impulsive and an overreaction. But more recent events have made many people in London wish that the British Foreign Office had reacted with equal impulsiveness. Nigeria, it seemed, was one country which understood what diplomatic relations were about, and had no truck with the abuse of diplomatic privilege.That, however, was the Nigerian government of President Shagari, in which Dr Umaru Dikko was minister of transport. The Nigerian government of today appears to have rather different standards. The External Affairs Ministry is now an address to which crates containing Dr Dikko and others can be sent.

The Nigerian government's denial of involvement will be believed by no one. Its anxiety to bring Dr Dikko to trial is well-known, and its chances of obtaining his extradition were negligible so long as he was likely to be tried in camera by a military tribunal…