The Traffic In Stolen Art: Threat To National Treasures

by Ekpo Okpo Eyo

While there is nothing wrong with this argument in so far as it goes, it becomes questionable when we look at real situations.

Then one finds that the notion is good so long as art treasures flow in from the 'peripheries of the world' to the 'centre' and not from the 'centre' outwards. Benin bronzes should be seen in museums in New York and London but it is impossible to contemplate Leonardo's Mona Lisa or Velasquez Portrait of Juan de Paraja in Lagos or Accra. No, the risk involved would be too much, the paintings would disintegrate in the climate and, in any case, the natives would not have enough sensibility to appreciate such masterpieces.

Should you think that I have chosen extreme examples, consider the case of a Gothic ivory mask made in Benin, used there for three centuries and then plundered in 1897. It had remained in captivity in London for only 80 years but when in 1977 its return was requested for use as the emblem of the entire Black peoples, assembled in Lagos for the Second World Black and African Festival of the Arts and Culture (FESTAC), the British. Museum argued that it was too fragile to travel by air to Lagos and that the climate of Lagos was too unsuitable for it.

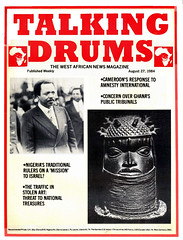

The point is that Third World count- ries are being systematically deprived of their cultural heritage and also being exploited economically. Artefacts, including objects of veneration torn from their spiritual homes, adorn show-cases in museums and private homes in major capitals of the Industrialized World. A Benin memorial head in a show-case in New York does not mean any more to the American public than that it is a memorial head of a 'tribal' king. But this head was made as a documentation of a particular king and occupies a particular position in the history of the Benin people. Its removal produces a vacuum in Benin history.

If follows that with so many Benin memorial heads removed from their home, the means of reconstructing or of illustrating the history of the Benin kings and kingdom has been destroyed. In this way, museums of the Western World, are in fact destroying the authentic sources of the very information they wish to disseminate.

In the past, the sources of museum collections in Europe and America were missionaries, explorers, scientists and colonial administrators. In many cases, objects collected were well documented, in other cases not so well or incorrectly documented. In the last several decades, this situation has become different and worse. Now it is almost completely confined to econ- omic exploitation through organized thefts. The sole purpose is to make money out of the heritage of the poor nations of the world. Here are a few recent cases from Nigeria.

A female Jebba figure, made in bronze, is the tallest in that medium yet recorded in Africa. In 1972, when I had just become Director of Antiquit- ies in Nigeria, the Jebba figure was one of nine such works scattered among several villages along the banks of the River Niger. All of the figures were associated with Tsoede, the legendary founder of the Nupe Kingdom and were tentatively dated to the 16th century.

In these villages the bronzes were the foci of religious activities in which every villager took part. As such, the bronzes represented the collectivity of the people. The Jebba figure was kept in a small mud house and, by arrange- ment with the local chief, the Department of Antiquities provided a care- taker to look after its safety. It was the normal practice for our staff to carry out inspection of these objects at least once a year. In 1972, after inspection had already taken place of eight of the bronzes, I received a cable from the Director of the Tervuren Museum in Brussels say- ing that the Jebba figure was being offered for sale. We rushed to Jebba to discover that a thief had entered the house where the figure was kept through a backroom window and re- moved it. A trip to Brussels failed to yield any more information other than the object was in Paris. No one was willing to say more. The figure has not reappeared and the people have been deprived of their object of worship. The figure has yet to surface, probably because so much has been published about it. The eight remaining figures have had to be removed by us and copies substituted. In sum, the people of Jebba have been deprived of their cult object, Nigeria has been robbed of a national art treasure and the museums of Europe and America have no new information for mankind.

Another case: the exhibition 'Treasures of Ancient Nigeria: Legacy of 2000 Years' (now on in Paris) was first shown in Detroit in 1980. It toured eight American cities, then went to Calgary in Canada. The exhibition was organized not only to dispel popular misconceptions about African art, particularly the notion that creativity is the monopoly of any one nation, but also to share with the world in the proper manner the joy that art lovers derive when they encounter great works of art.

When the show opened in Calgary, a couple of Africans, together with a notorious New York dealer, went to Calgary to sell an ancient terracotta figure belonging to a culture which has been dated to between 900 B.C. and 200 A.D. The Director of the Glenbow museum in which the exhibition was taking place, Mr Duncan Cameron, was embarrassed to be offered the terracotta which could only have been stolen. He had sat as an expert on various committees which worked on the 1970 Unesco Convention on trafficking in cultural property and on the convention on the restitution of cultur- al property to its country of origin.

As Canada is a signatory to both conventions, Cameron thought this was the chance to test the convention. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police were alerted and the would-be vendors arrested. Although the case is yet to be settled, this is the first time that the 1970 Unesco convention is being tested in a court of law.

Those acquainted with the looting of art treasures in Africa are familiar with the infamous British punitive expedition to Benin City in 1897. In this operation, the King's Palace, in which bronzes were kept, was burnt down, the bronzes taken away and the king banished to die in exile.

Benin bronzes have been bought and brought back to Nigerian museums but Benin Museum itself has to display third rate pieces and casts and photographs of works which adorn other museums. Before 1981, there may have been isolated cases of thefts of museum objects from Nigeria, but by and large, the museums were not places to go, as in some African countries, to acquire objects. Now it is a different story, perhaps as a result of the awareness created by the 'Treasures of Ancient Nigeria' exhibition. The rise in theft from our museums is a story from which one may learn many lessons. There is the aspect of sharing the joy of art with the world which museums of Europe and North America have always advocated. There is the quest- ion of the nature of cooperation with art dealers. And finally, there is the dilemma of a museum director in the developing world. CONTACTING THE F.B.I. Sometime in 1980 I visited the Pace Gallery in New York. There I saw a Yoruba wooden figure with which I was familiar and which my predecessor, Kenneth Murray, had photographed in the field. When I got back to Lagos I checked in the archives: there was no mistake about it. So I sent copies of the documentation and a photograph of the figure to Pace, pointing out that the figure they were handling was illegally removed from Nigeria. Pace wrote back confirming that the piece was the same. But, they said, they had bought it in good faith. How were they to get their money back, they asked? My answer was that they should return the piece to whoever sold it to them and show him the documentary evidence which we had provided.

It was about six months before I heard again from Pace, and then not about the Yoruba figure. A cable arrived asking whether we had lost three Benin bronzes: a head connected with the cult of Oduduwa, a very fine fragment of a 16th century plaque and an aegis. The Oduduwa head was pretty well known but the museum numbers on all the pieces had been scratched out and their documentation destroyed. I telephoned Pace and asked for photographs which they immediately sent. With these, I was able to trace the pieces in the set of museum catalogues kept permanently in my office.

The Nigerian Security Organization was alerted and they in turn informed Interpol. But the vendor of the items, a Black American, was demanding a quick settlement with Pace or he would withdraw the items. So I decided to make contact directly with the American Federal Bureau of Investigation (F.B.I.) through the Nigerian Ambassador in Washington. As a result, the pieces were immediately taken into custody and the vendor arrested. He told the F.B.I. that the pieces had been offered to him in his hotel in Lagos. He did not know what they were worth. The people who sold him the pieces, he said, had arranged their packing and export permits.

I could have pressed for his prosecution but I thought it would be better to use him to get at the source of the theft since it looked like an inside job. The Black American whom I shall refer to as Mr Hogan, was given a free return ticket to Lagos and free hotel facilities for one week in order to help identify from among our staff the two men who sold the bronzes to him. He refused to participate in an open identification parade and asked instead for photographs of all members of staff. These were supplied but after a week nothing had come of it. Mr Hogan cautioned us to make haste slowly, otherwise we would scare away the culprits.

We decided to be patient but Mr Hogan refused to return to Nigeria the bronzes he had taken to America, although he had previously agreed to do so as a condition for not being prosecuted. He had enlisted the services of a lawyer who now demanded that the money Hogan had paid for the pieces, about $25,000, should be refunded to him before releasing them. The pieces were worth $600,000 in the open market. We continued to exercise patience until Hogan returned to Lagos and was immediately arrested by the Criminal Investigation Department. He then had no choice but to authorize the F.B.I. to release the pieces to me.

In the meantime, Pace informed me that another bronze, was about to leave Nigeria, a plaque illustrated in my book Two Thousand Years of Nigerian Art, (published by the Federal Department of Antiquities, Lagos, in 1977). After the first thefts we had taken an inventory and the plaque had been in a storeroom then. Six months later it was nowhere to be found and a second inventory was ordered.

While taking the second inventory we discovered two manholes in the ceiling of the storeroom carefully camouflaged. When the police arrived they found tracks leading to the locked office of a staff member who was accompanying the 'Treasures of Ancient Nigeria' exhibition. This man has since been arrested and the case is pending in court.

Now Pace knew, but would not disclose, where the bronze plaque had been taken. Rather they offered to get it back for us if we would refund the money paid by the person who had bought it. This was $35,000 while the worth of the piece in the open market would be $400,000 to $500,000. This posed the problem of whether we should pay money to regain what had been stolen from our museum. I had planned to circulate internationally photographs of the plaque but was advised that if I did so, the plaque would disappear forever and possibly be melted down. Eventually, after lengthy discussions with the government, we obtained the money.

One factor which led the government to provide the $35,000 was a similar incident which had occurred early in 1980. Sotheby, the international auction house, had advertised the sale of a fine Ife terracotta head. I had written to them that the head was stolen from Nigeria and that it would do them no good to be associated with the sale of property known to be stolen.

The piece was withdrawn and returned to the 'owner' who had put it into the sale. When the Nigerian exhibition opened in Detroit in January 1980, a man telephoned me at my hotel and asked if I would consider buying the piece for Nigeria as I had succeeded in stopping its sale. If I was interested, some other person would call me to discuss terms. I did not know. what to say. Then ten minutes later a woman called and told me that the piece had been taken out of Nigeria by a missionary 30 years earlier, and that she had sent it to Sotheby because she wanted a public museum to buy it.

She was prepared, she said, to let the Nigerian government have it for $150,000. I raged and pointed out how improper it was for us to pay for a treasure stolen from our territory. The woman then wanted to know what she should do with the piece. I told her she could do what she liked, even, if she wished grind it to powder, mix it with water and drink it so that the head would forever belong to her. She thought I was the most callous museum director alive. The piece has not surfaced since then.

The cases I have cited show how vulnerable museums, let alone unprotected shrines and temples, can be in Third World countries. It must be obvious that the way to protect art treasures in the developing countries is not simply to tell them to take protective measures. As long as there is a ready market in Europe and North America, stealing will not stop. Nigeria, for example, has a vast national frontier which it would be prohibitively expensive to police against trafficking. Even if we were able to afford it, the attraction of easy money can corrupt law enforcement officials.

No one would quarrel if museums at the 'centre' of the world asked quest- ions about the provenance of objects which come to them. If museums buy properly, art trafficking would be reduced to a minimum. For no matter how rich a collector may be, even a collector who does not require money from selling items in his collection, eventually all works end up in public institutions. So it is by refusing to buy what is illegally offered that we can hope to take the wind out of a trade which is not only immoral but is slowly and steadily wiping out the most authentic evidence the peoples of the Third World have of their 'Being'. As Ava Plakins wrote in New York monthly Connoisseur of January 1983: "It all makes one wonder how much artwork finds its way out of less cautious museums and countries and into the hands of less discriminating dealers".

It makes one wonder, too, how much artwork finds its way from less discriminating dealers to museums equally lacking in discrimination.