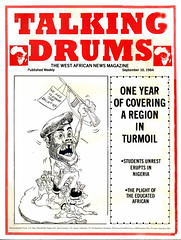

The Plight Of The Educated African

Dorothy V. Smith

Readers should note that the writer is aware of numerous generalizations in this article about Africans and Europeans. However, the basic information is correct and the points raised are the same, regardless of whether they are Ghanaian or Nigerian, English or French. Essentially, the article will explore several means by which Arabs and Europeans were able to maintain control of Africa.The belief that education could, and would, generally produce the key to knowledge, mobility and a future of happiness has recently come under a great deal of scrutiny. This notion is also quite true in Africa, especially among those seen as Revolutionaries and Nationalists. Consequently, some critical questions have been posed which must ultimately be addressed: are Africans being educated abroad in order to return to their societies as useful members, or is the goal to educate these Africans who may merely serve as power-brokers and, in the end, to make sure that the status quo is maintained?

The road to future success starts in the classroom, or so at least these attentive pupils hope.

Dorothy V. Smith is a Doctoral Candidate in History at the University of Kansas; she also teaches History at Dillard University in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

Historically, Africans have been extremely interested in educational pursuits which date back to the great University of Sancore, in Timbuktu. Although this ancient academic institution of higher learning was operated and controlled primarily by the Muslims, it is an undeniable fact that Africans attended it in large numbers as part of the attempt to elevate themselves. In that period, Muslims controlled the economy, while Islam was the dominant religion of West Africa.

Interestingly, the educated African was eventually in a position to interpret and read for the ruling Sultan, thus bringing prestige and rewards to the former and his family. However, it also meant that in order to receive what was being considered booty, conces- sions had to be made on the part of Africans. Above all, while Africans understood the Islamic requirements of attending the University, their desire to receive an education was paramount.

Africans became spiritually indoctrinated in the Islamic culture and, whether consciously or unconsciously, the seeds for the separation of the African family were sown during this period. Then, in order to become a pious Muslim, one had to speak the Arab language, and to assume an Arab name. This measure of accommodationism caused immediate and future problems of serious magnitude for the Africans. As Muslim domination came to an end in the 13th century, a new but even more domineering group seized power.

The rationale for Europeans coming to Africa rested primarily on their desire for power and, once on the continent, they began the gradual phasing in of their policies. Although these Europeans understood very little about African society and its class and race distinctions, they were able to start their subjugation of the people.

As part of the controlling mechanism, different laws were applied in various parts of Africa, in most instances depending on which European masters did the colonization. However, the goal of all the colonizers was, nevertheless, their superiority, and one of the best ways to advance that aim was through the educational system. As a result, they organized various educational institutional systems modelled after the ones in Europe.

In order to subjugate the Africans further, it was quite possible for an African to complete all requirements needed for a particular level of study and, yet, know nothing about African history and geography. After years of this mode of mis-education, some steps had to be taken to rectify the anomaly.

The late 1950s and early 1960s ushered in a new era in African educational research and development. There was a political and social awakening which stemmed from the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Despite the Trevor Ropers of the world, African History now took on an entirely new and serious dimension for colleges and universities worldwide to commence the task of re-organizing their curricula to embrace these courses.

To a great extent, the introduction of African History courses into the existing curricula was done in a way which was similar to what had been done earlier in the period of slavery; basically to calm the revolutionaries down. The tactics were, however, different but the message was the same, as courses were to be added and, at the same time, firmly controlled by the colonial educational bosses. To a large measure, it was a sort of contract but in the interim, between the new master and the new "educated slave".

Obviously, the drawbacks were numerous but, perhaps, one of the greatest concerns was about the avail- ability of teachers to teach the new courses. In the beginning, it was taught by whites because they happened to have access to the needed materials and, invariably, they could get books published on the subject to attract the accolade of an authority. This was despite the fact that they were the ones who least understood the African society.

Sadly enough, after a number of years of calculated under-education of Africans, the white masters ultimately produced a group of Africans that they deemed qualified to teach African History. This, of course, was a mixed blessing, since on the one hand there were those whose visions of Africa went far beyond those of their former teachers and, on the other hand, those who held steadfast to the lessons they had learned from the teachers.

The latter group began the cultural and educational commission of crimes equal to, if not greater than those of their predecessors. Africans were. therefore, now being emasculated by blacks and whites. Interestingly, Africans in most instances, wanted to be taught by fellow Africans, and the new African teacher had a familiar voice and face to his students. Above all, he was reassuring, comforting, and welcomed with open arms, but his thoughts were often alien.

It is a fact that a student's spirit was enlivened by the lightness and the spirit of the teacher, but there was something strange and un-African about him. He had the language and mannerism of home, and his face bore African markings, yet he was different as he no longer thought and responded like his own people. Perhaps his shortcomings stemmed from the way he moved so very easily from one topic to another, and the fact that for him customs and boundaries mattered not. To a large measure, he seemed to understand and relate to everything European but to condemn everything that was Pan African, while his eyes often search among his students to find the one who would be able to continue his marvellous job of mis-educating future generations. This was not the kind of education the African either wanted or expected, because it was something strange and new; unfortunately, it was exploitation by his brother under the guise of education.

To a great extent, the introduction of African History courses into the existing curricula was done in a way which was similar to what had been done earlier in the period of slavery; basically to calm the revolutionaries down. The tactics were, however, different but the message was the same.Very often, the item which separated a good African scholar from a poor one was language. This, too, became a tool of oppression and mis-education of Africans. Understandably, language is a way of bringing people together, but it is also a way of separating them, and language did bring diverse African words into the English, French, or Spanish-based Creole languages. Also, language is a way of maintaining social distance among people and it perfor- med similar unhelpful roles in the African tongues.

Indeed, Europeans and Africans had always made distinctions among themselves by how one used words. The higher orders marked themselves off from the lower ones by accent, tone, diction and vocabulary. Therefore, in Africa, African speech and European speech became marks of social disparity, and those Africans who did master the white man's language very well were, in so doing, placing themselves socially at a distance from those Africans who did not.

As a matter of fact, how an African would come to speak the English language would depend on more than an opportunity, intelligence and facility. In most instances, there needed to be a choice to emulate white people, the ability to step from one style of speech into another when the occasion warranted, and the willingness to bear the ridicule of fellow Africans who might see him as a mimic and sycophant, or as merely accepting the white man's way of life.

White people, however, were anxious to keep their language to themselves. They invariably wanted it as an emblem of the social superiority they felt to Africans and the lower orders. They wanted to talk to one another, among Africans, and not have their true meaning and intentions understood. They wanted language to serve as a limited way of communicating between themselves and Africans, but they also wanted it to remain enigmatic. Language, to them, was a mark of civilization as well as a tool of communication, and they needed the sense of security that a monopoly on good speech and literacy gave them.

Furthermore, they knew that language transported ideas, and ideas could be weapons against the estab- lished order. So, rather than finding a prideful and missionizing achievement in the acculturation of Africans into European languages, the whites were protective and jealous. Above all, many Africans were to be kept ignorant as far as possible, while those educated were to become Europeanized rather than Africanized. This act of cultural genocide ranks as one of the greatest sins of African History.

Similar to the educational process, the socialization of Africans worked in a similar manner, as one was constantly being torn by indigenous customs and European laws. The educated African, therefore, faced a difficult future, and would never genuinely be fully a part of his society again, but also with the obvious realization that he would be rejected in European society. What, then, had education done to him?

For some of the educated Africans, it meant an opportunity to try and find peace of mind, but to others it was cultural torture. For those willing to travel outside, scholarships from various sources were often available.

As the trend to open the system to Western intellectual traditions increased, it became more difficult for the state to maintain control over African intellectuals. Indeed, both the left-wing and right-wing ideas infiltrated the educational system and created a climate in which the, supposedly, superiority of the European could no longer be taken for granted. Struggles developed between the intellectuals and the colonialist over the direction in which education could take. This was not simply an academic argument but, instead, a disagreement over the role of higher education in the development of the newly independent African States as modern nations.

The 1960s, in fact, witnessed intellectual unrest in many parts of Africa. While there were many reasons to take direct action at this time, the real issue at stake was much broader than the control of educational institutions. To an extent, the fight was about the ending of colonialism, and the Africans won out in the end, but not without a bitter struggle.

The liberation of Africa from the hands of the colonialist produced the opportunity for the support of a new ideology. For the war had been won, but the struggle continued. In order to change the system, minds and attitudes had to be changed and, as a result, it became necessary to detain, dismiss, or silence individuals who represented a threat to the new way of life. While many obstacles, including neo-colonalism in education and politics remain to be solved, the hope for a brighter future based on a genuine education for the benefit of Africans is now stronger than ever before.