Soldiers and politics: the case of Ghana

Kodwo Mbir Bullard, Los Angeles

Commenting on the recent escalation of prices of food and other essential commodities in Nigeria, Brigadier Tunde Idiagbon, Chief of Staff, is reported to have put the blame on "the nefarious activities of middlemen and smugglers who instead of helping the government to get the essential commodities to the common man, collect the items only to make them available to friends, relations and even smugglers". This is a familiar lamentation.

This frustration and attitude exposes the ignorance and naivety of our modern African soldiers who think they can do a better job at ruling our countries than the elected representatives of the people. These soldiers subsequently seize power from the politicians, shout themselves hoarse with denunciations of the overthrown regime and promises of heaven on earth. It does not take long, however, for these self-appointed soldier messiahs to realise that they are as powerless as the politicians they overthrew in dealing with the same problems, especially those relating to price controls.

The soldiers resort to threats, beatings and in moments of total loss of control over themselves and over the situation at hand, they bomb markets and indulge in other dramatics. They prefer to grapple and fight with the SYMPTOMS, either totally ignoring or completely ignorant of the basic causes of the problems.

The issue of price controls, especially of food, has been a thorny one for many a country. Experience with dealing with this problem is ample and is there for all to see. This experience, which is very current and at the same time well-documented, demonstrates how ineffectual, approaches like threats, beatings, bombings or exhortations to one's patriotism and good nature etc, are in solving the problem of high prices.

The truth of the matter is that in a situation of SHORTAGES, no matter what one may wish or decree, prices go up. Conversely, in a situation of relative abundance, in order to avoid losses, sellers will reduce their prices. In other words supply and demand always dictate prices. The factors that in turn influence supply and demand are many, but none is subject to threats or exhortations.

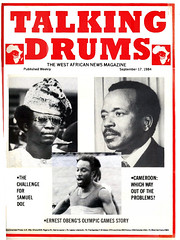

Jerry Rawlings of Ghana, after brutalizing and terrorizing Ghanaians, and disrupting the lives of many for two and a half years, has gone one full circle. After unleashing thugs in the form of PDCs and WDCs to enforce wildly unrealistic prices, has now virtually come to accept as inevitable, the situation that he found unacceptable in 1981 and which led him, among several other reasons, to overthrow the Limann administration. He is now allowing prices to find their own levels.

At this stage, we will credit Rawlings for heeding the famous adage, that the most dangerous folly is not error in the first place, but refusal to turn back from it. But Rawlings should not stop to mature. there. He should pursue that strategy further and reduce drastically those ridiculously high import duties on the basic goods that the Ghanaian economy is not producing now nor is capable of producing in the very near future. Of course, luxury items like Rolls Royces and Mercedes Benz 600 etc, should continue to attract very high duties if not completely banned. We are better off without them since they are gas guzzlers.

But the fundamental question still remains: Does Rawlings or any soldier for that matter, have the right, moral or otherwise, to inflict such havoc on a hapless people in pursuit of a personal ideal which has turned out to be no more than a mirage, AFTER ALL?

Come to think of it, the turn-around is an admission of failure, at least in the economic sphere.

Have there been any gains on the political front? Have any institutions been brought into being that ensure the effective involvement of the common people, the working classes, i.e., the mass of the peasantry, in the day to day decision-making of the country? I am not talking about decisions that are taken adhocly, based purely on malice and wickedness, and which cannot be justified on any economically rational grounds. Have any clear-cut procedures been laid down that ensure the orderly adoption, implementation and evaluation of policies and programmes?

I am not talking about budgets that are drawn up in Accra by desk-bound theoreticians, presented for discussion at a three-day seminar, and approved by acclamation. Do the citizens have the confidence that their personal lives are not threatened through the arbitrary and callous use of power? One can multiply these questions. But in short, do Ghanaians feel that they are better off socially and politically today than they were nearly three years ago?

If the answers to all these questions are negative, then the last three years have been a monumental waste of time, very precious time during which well-tried and tested, well-known democratic institutions and processes could have been developed and allowed

It seems to me that one of the important lessons that the events of the last three years should have taught us is that life is too precious and too short to waste through unnecessary experimentation and adhocism.

There is nothing wrong with experimentation per se. But experimentation with ideologies and philosophies that are not clear even to the proponents themselves can be very dangerous and should be discouraged at all cost.

Governments can be made more responsive to the needs of the citizenry without unnecessary disruptions in the day-to-day run of things. The Judiciary can be made sensitive to basic human values and human sensibilities without their members being subjected to banditry. kidnapping and murder. The legislature, the management of public corporations and all public institutions can be made more responsible and accountable without the need for threats and blackmail.

Nation-building has never been a one-man endeavour. It requires a massive effort on the part of all and sundry: the educated and the less educated, the skilled and the unskilled, the high and the low, in more classical jargon, it requires the joint efforts of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The processes are slow and may be genuinely painful at times. But when allowed to work themselves out. traditions, institutions and procedures do emerge that ensure not the creation of heaven on earth, but life that is less arduous and more worth living than it would otherwise have been.