Profile Of A Sovereign People: "Ghana, Here Are Us"

By Ebow Daniel

senior registrar, University of Ghana, Legon.

Optimism suffuses Ghana. It does not matter how long the queues for anything grow to be, everybody appreciates that the inconvenience is only temporary, and our manner of expressing this faith is refreshingly exciting, "no alarm for cause"!The other day the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, Legon, held a seminar on the subject "Who are the Guans?" An earlier seminar sought to find out who the Brongs are. Evidently, who are Brongs or Guans is hardly the settled matter that the unwary might suppose. Other questions for which there appear to be ready answers may as well be raised now: Do Guans, Brongs et cetera feel Ghanaian?

Back in Guan or Brong country, everybody knows his place; set procedures and protocol with which everybody identifies have evolved such that abrupt changes are not readily appreciated. Things are far from being settled in the larger community that is Ghana; worse we do not seem to care. So, besides being Guan or Brong, do we also feel Ghanaian?

It was not always clear that the protectorate of the Northern Territories or Ashanti, the latter a conquered territory, would join the Gold Coast Colony to the south to form one nation. It was not until 1946, with independence barely a decade away, that representatives from Ashanti arrived on the coast to participate in the Legislature of the Gold Coast Colony; representatives from the north came later still, 1951. Nor was it ever certain that the former British Togoland would be part of Ghana until the UN-supervised plebiscite of 1956.

All this is to say that Ghana is not historically homogenous. Certainly, if the outcome of the UN-supervised plebiscite of 1956 had been different, many who now live in the former British Togoland would be anything but Ghanaian nationals.

On the other hand, considerable inroads had nearly been made further north of today's Upper Region in the last until being caught in the cross-fire between Samori Ture's warriors on one hand and Gallic Imperialism on the other, the team of surveyors that went up from the south measuring and claiming lands and beat the retreat.

Even now, there are at work various international border demarcation commissions whose decisions could affect the composition of the population. That the people living near the borders probably have more in common with the "alien" across the border than with the inland compatriot is conceivable enough, if the following anecdotes tell anything.

A "Ghanaian" diplomat in Europe who fell victim to one of the purges of the Public Service that herald every new Administration had only to walk to the next block to retain his diplomatic status, and he felt as much at home in the new place as in his previous employment.

Given a people so accidentally brought together with some of them still retaining ties with others outside the geographical area, a uniform response to national events could hardly be expected.

His father had been native of one country, his mother the other; born in one country, he had grown up attending school in the other; it did not take much to go from one country to the other and the occasions for going and coming were many, among them, funerals, weddings, festivals; the native tongue was the same in both places; and proficiency in two European languages was his privilege as a child of two worlds. If he could be First Secretary in one world why not in the other?

A similar case is that of the Colonel who while commanding a section of Ghana's armed forces lately was a regular guest at an Embassy in Accra. His Excellency the Ambassador and the Colonel, indeed, had reason for getting together if only to discuss family matters.

They were brothers, same parents, same name and all, though of different nationalities! The point is that having to go across the border early in childhood to live with a well-to-do relation who may have crossed the border a generation earlier, or some such chance event, often divides a family significantly beyond immediate appreciation.

Given a people so accidentally brought together with some of them still retaining ties with others outside the geographical area, a uniform response to national events could peoples for British Imperialism had to hardly be expected, nor should a positive identification with national institutions be taken for granted. If we cared enough, however, we might begin to look for those things that uniquely belong to all of us on the basis of which identification with one another could begin in earnest.

In this we have the success story of the United States of America for cheer. Though comprising a large variety of ethnic groups, the people of that large country are still able to identify with one another; living together in the same geographical area helps, no doubt; so does common pride in the federal constitution of the United States with its several amendments uniquely designed to guarantee some measure of individuality in a polyglot community, but perhaps common fondness of bubble gum, coca cola, Ford Motors and baseball is the more enduring bond.

To foster national unity some new nations contrive to make even national sporting teams representative of the constituent ethnic groups; the presidency or prime ministership must rotate so that the whole population begins to identify with the institution.

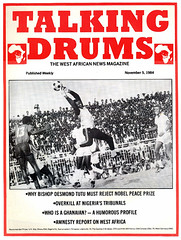

In Ghana, a rotary presidency is not yet formally the case, nor does selection of the national football team, the Black Stars, take cognizance of ethnic representation, but the Black Stars manage to win matches and in the enjoyment of the team's brilliant successes on the African continent we are all united.

Ghana's pride in the successes of the Black Stars is paralleled only by initial elation over Ghana Airways; that a black nation could run an airline managed and piloted entirely by Ghanaians was a source of tremendous satisfaction. Ghana Airways is now practically reduced to a single carrier, one which goes further than no London, but not a few have remarked the advantage to national cohesion even in this: "One country, one DC10, one destination, Accra-London-Accra!"

Partly from living within the same geographical and running a single-plane airline, characteristics and phenomena that uniquely identify Ghanaians are observable already.

Optimism suffuses Ghana. It does not matter how long the queues for anything grow to be, everybody appreciates that the inconvenience is only temporary, and our manner of expressing this faith is refreshingly exciting, "no alarm for cause"!

Of course, queues do not portend the end of the world, that too is well appreciated. Accra Hearts of Oak, the oldest football club in the land, has a song which says it all, something about "never saying die, until the bones are rotten".

And we insist on enquiring about the state of the bones at every turn: "How is the going?" in nearly all of Ghana's languages the response has come to be "it's all right" or that "It's going to be all right". And the respondent might be under considerable strain indeed. The idea is not to succumb to adversity.

Playing down adversity is a national proclivity of which not everybody approves, not Bob Cole, the comedian- songster who is everybody's favourite:

Don't ask me how it is at homeIn spite, however, of Bob Cole, every beleaguered compatriot still answers "it's going to be alright" to greetings, believing help is just round the corner; indeed that the person offering greetings brings relief; and so a variant to "it's going to be alright" has come about: "We are looking up to you"!

Seeing clearly I am handcuffed

And escorted by a policeman

Besides being optimists, Ghanaians are a hospitable people. Recollection lingers of many a visitor leaving the country laden with gifts of kente, hand-made sandals, even carved stools to sit on; of freedom fighters looking for support, moral and material, and getting both; of emerging new states receiving the initial endowment to speed them on to sovereignty.

But there are other features of Ghana's peculiar make-up that are no less striking. Our politics is distinguished by a rather desperate search for a system of government that is uniquely ours. The dominant idea in this search refers to a single-minded approach to governing (as against the Government versus Opposition syndrome).Among ourselves, the entertainment bill of governing boards of public corporations alone was always enough to build additional hospitals and schools. The kitchen used to be the busiest section of any state enterprise, ensuring the "happiness" end of the "Work and Happiness" development programme launched in the sixties. The end-of-year bonus to staff of public corporations had to be paid willy-nilly; borrowing to pay was often the most convenient arrangement in the year no profits could be recorded.

In pursuit of happiness it was only natural that the inauguration of the Second Republic should be marked by a state banquet. The Prime Minister spoke at the banquet referring to the nation's depleting resources and our indebtedness to all and sundry, quickly adding this was no reason to deny ourselves the occasional banquet seeing that the debtor too must eat.

If ever wining and dining while the debts piled up occasioned embarrassment not since the Prime Minister spoke at that banquet recalling, as he did, that most profound saying of the Akans: Kafo didi. "Sure, sure", the Prime Minister's audience roared approval.

But there are other features of Ghana's peculiar make-up that are no less striking. Our politics is distinguished by a rather desperate search for a system of government that is uniquely ours. The dominant idea in this search refers to a single-minded approach to governing (as against the Government versus Opposition syndrome).

Initially, the single party system seemed to hold a lot of fascination, but the whole idea of a political party turns out to be foreign in origin besides being needlessly divisive. On the other hand, the no-party system is increasingly coming to be seen as a more accurate reflection of the dynamics of the traditional society. "Union Government" (Unigov) which was to have been the prototype of the no- party system in action proposed a sharing of power among society's more visible categories (army, police and civilians!) to arrest mutual antagonism between them. Although Unigov proved still-born, the no-party concept is far from dead.

In spite of all efforts towards monolithism the body-politic ironically remains as polarised as ever: Progressives versus Reactionaries; Socialists versus Capitalists; The Military versus Civilian Politicians. The division comes often to refer to the Good versus the Bad; who gets which epithet is a matter for the press; and whatever anyone's misgivings may be, it cannot be said of the press in Ghana that it does not know how to play up to "who pays the piper".

Truly, every sovereign people deserves the press it gets as much as its top public servants. To reach the very top of the public service evidence of commitment is required. Commitment often reveals itself first in the long memorandum covertly sent to offer advice to an incoming Administration.

The memorandum also serves to bring the peculiar merits of its author to official attention; an interview on Radio Ghana or Ghana Television or a mere letter to the newspapers condemning the previous Administration serves the same purpose. Eventual appointment as Minister of State or an Ambassador has to be explained to friends if it occasions astonishment: "the national interest suffers if good people would not accept office."

Apprehending yesterday's men for misdemeanours freshly discovered is a test of commitment easily passed by Ghana's law enforcement personnel. Outside the corridors of law enforcement committed people are to be found also on the shopping floor of the Ghana National Trading Corporation. The females of that Corporation used to wear bright lipstick and a smile to detain the customer on the shopfloor as long as possible, not letting anyone go until something was bought.

There being not enough of anything to go round these days, the commitment is now keeping customers at bay. Significantly, the smile has disappeared, even if a smudge of lipstick remains, and monosyllabic answers await who comes asking for soap, sugar, milk or other items of "essential commodities."

Nor is the customer any more welcome at the Post Office where, to renew a driving licence, the exact change is required, not a pesewa more unless it is for "dash." As for Ghana Commercial Bank, monies being paid in had better be arranged "properly", heads to one side, tails the other! Whose idea is this unique banking practice? The cashiers have no time for questions. Would the customer asking questions stand aside for others who know the rules to come up?

Knowing the rules of banking in Ghana must be as troublesome as speaking English the way Ghana likes the language spoken. The captain of a visiting athletic team from a neighbouring country is said to have announced his team at a reception in that memorable quote which introduces this piece, "here are us", which particular example of linguistic aberration has never failed to amuse Ghanaians.

To the delight of Ghanaian audiences, a Ghanaian professor at the University of Ghana, Legon, also reports of a former Dean, an Eastern European, ever so polite and so anxious not to disturb anyone's routine, he would write circulars inviting the faculty to a discussion "for several minutes only"; for every good turn, the Dean always had a token something (a pen, a pencil, an almanac or a diary) to give "in revenge!" The above is all too reminiscent of the story of the two earthenware cooking pots, one ridiculing the other for being dirty with soot, little realising the joke was on itself as well. Ghana's linguistic pot always carried a new shine, the latest in linguistic fashion. To disperse the queues that other time, up: an official from the Consumers Ministry came on television to assure the public there was rice in the system. Why not in the market? The official gave a long explanation all to the effect that somewhere along the line somebody had failed to deliver.

Not all Ghanaians are enamoured of systems of stilted speech that may be delivered somewhere along the line, happily. Many prefer to speak more directly rather like the man-about-town who had to testify in the High Court the other day. Asked in Fanti by the Court Clerk whether he would testify in Fanti or English the man was visibly pained: "What me? It will speak English, whereupon a jingle went

Wears the whiteman's clothesEver ready with song, optimistic and hospitable, a people committed to finding unique ways of doing things and by no means dull of speech Ghanaians have travelled a long road since Independence, 1957, and now to borrow another's expression, "HERE ARE US"!

Can't speak English

Can't speak English

Still wears the whiteman's clothes.