Whispering Drums With Maigani

by Musa Ibrahim

Civil rule debate

Arguing that the coup was premature because the politicians had not been given enough time and the benefit of the doubt, Adoko prophesized that it will not be long before the military leaders become saddled with the same problems that had bedevilled the politicians. Events in Nigeria today have proved the Kenyan no mean judge. And now, rather than face squarely their own follies and try to undo some of the damages wrought against the Nigerian populace, the Buhari military junta is trying to take the easy way out - hand-over a chaotic, confused, dis-oriented nation back to the politicians.

It is the military's traditional way of buck-passing or escaping blame. They have been using this ploy successfully ever since they became politicised.

The logic seems to be that in the best of times, only the soldiers are capable of governing, but when all is not well it is a work for the politicians. For instance, when Gowon announced his nine-point programme in 1970 for a return to civil rule in 1976, he had not adequately taken into account certain factors, one of which was petroleum.

Soon after Gowon's announcement for a return to civil rule, income from petroleum started growing faster than other sources of revenue, thus opening new visions of wealth to the military decision-makers. Three years later, Gowon announced that the target date, 1976, was "unrealistic". When the Murtala-Obasanjo regime came in, revenue from oil had diminished quite dramatically and there was less money in its foreign reserves. Following in the profligacy of its predecessor, the regime exhausted all that was left in the national treasury and for fear of being found out, quickly handed-over political power and an empty treasury to the unsuspecting politicians.

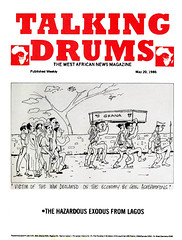

Battling with oil glut and all the other paraphernalia and oddities that accompany party politics, the Shagari administration had managed to set a firm course towards economic recovery only to be overthrown soon after. The Buhari regime has completely fooled the nation and emptied the treasury and now they are demanding that they be left to go, hence the debate now on the next appropriate political system for the country. In other words, Nigerians are being asked to look for an alternative model for the country's political development.

So far three views have been put across.

Beneficiaries of the Buhari military junta have called on the regime to convert the administration into a one party state with Buhari as president, without the holding of any elections. As would be recalled, Gowon also contemplated this option during his hey-days. This thesis is aimed at the validation of military intervention and military rule not only in Nigeria but the entire continent of Africa. Advocates of this option are of the opinion that Africa's elite, i.e. those that took over power at the time of independence are the architects of Africa's instability.

Arguing that a good many of these elites had their education at the metropolitan centres where they were exposed to alien cultures, the elite are therefore alienated from the indigen- ous cultural heritage and cut off from the masses and so cannot govern them. The military on the other hand, is seen by these theorists as the only institution that shares the same cultural idiom with the people, particularly the workers, and are therefore in a better position to effectively govern the people. I am sure the Nigerian workers will choke.

Plausible as this thesis may seem on the surface, this becomes no more than a mere assertion when the reality is confronted.

If the military can be said to be culturally closer to the people than the elite, it is not because the military, unlike the elite, have not been exposed to the alienating impact of a foreign culture, rather it is because the military are yet to be freed from the bonds of illiteracy which still continue to handicap the mass of the African population.

And it must surely be an odd argument which would seek to justify a system of rule by the largely non- literate. Besides, with the possession by the military of the instruments of coercion, the people's so-called allegiance to the military rulers have always been out of fear of repression and victimization rather than from the love of the military.

The second view calls for the institution of a (political) system in which power will be shared between the military and an elected civilian element but with the military holding a veto power. Advocates of this system call it dyarchy. A final option which is shared by the majority of the populace is an unconditional handing-over of political power to a popularly elected civilian government as happened in 1979.

Proponents of this last option must have been aware of the sociology of the division of labour that exists in all sane societies. The bone of contention here is that in every society, various groups exist to cater for the diverse interests and needs of a community or a nation. In other words, individuals normally have distinct functions or roles to perform in the growth and development of a society based on their training, and that as long as there are no role conflicts, then there is bound to be order and stability in that given country.

Instability and conflicts arise however, when one professional grouping tries to usurp and take upon itself the functions and duties of another professional grouping that it knows nothing about. It is often the case when soldiers usurp constitutional governments.

Even though in the final analysis there still may be no way of preventing the military from seizing political power for as long as they have a superiority in the means of mass destruction, nobody in his right frame of mind should go out of his way to try to justify such seizures which are often violent and bloody.

African governments should not be transformed into card-houses. They must be built to survive the destructive threats from all institutions in their countries.