The Ghanaian greenback: Its symbols of identification

by Ato Imbeah

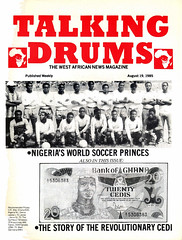

The Ghanaian "greenback", whatever its worth in monetary terms, tells a whole story about present day Ghana and the realities of the revolution. ATO IMBEAH examines the alignments of power in the social hierarchy the stories behind the illustrations on the twenty-cedi note.The new Ghana twenty cedi note is already being referred to in some quarters as 'Ghana's Greenback', although those who coined the phrase know that it cannot compare with the American Greenback', the dollarnote.

It is not only that the 'American Greenback' issued during the outbreak of its civil war surpasses the "Ghanaian Greenback" issued in 1984 in years, but also that the dollar is an acceptable international currency or a reserve currency which enjoys the confidence of the Americans in its control of issue and uniform standard, these being essential for an efficient system. Anyone who handles the 'Ghanaian Greenback' will concede the fact that when a large suitcase is necessary to carry the purchase price of a refrigerator, then obviously there is something wrong with the system.

The 'Ghanaian Greenback' satisfies the basic aim of any monetary system though, that is, to remove the dilemma implicit in the system of barter, as prices, no matter how high, are set which both the buyer and seller accept as fair, and the seller can use or save to buy whatever he wants; in other words, it has value at least in Ghana.

One striking feature of the twenty cedi note is the symbol of identification which makes the note legitimate. On the front part of it is the bust of Yaa Asantewa, a queenmother of the Ashanti nation who died in 1923.

Queenmother Yaa Asantewa is famous, but not because she ruledGhana or the then Gold Coast. She is more remembered for her revolutionary stand against the British when a determined attempt was made to amalgamate the Ashanti Kingdom with the Southern Region at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The symbol of identification on the backside of the twenty cedi note is even more remarkable. It shows a miner, an army officer, an academician, and a hand clutching a fly whisk, a group that has now come to be known in Ghanaian circles as the "Establishment".

Below these elites of Ghanaian society are the masses armed with bows and arrows, pick axes, spears, sticks, matchets, guns, and others with clenched fists marching to the beating of drums.

As the bust of Yaa Asentewa on the front side may be an honour to her memory, the picture on the backside seems to give official stamp to the fact that if nobody else is willing to ex- change the twenty cedi note for goods and services, the people of Ghana who are represented thus will exchange them, and that they are ready to help the currency of their country keep its value through the international credit rating given to its productive strength in producing goods, in selling services,and in making profitable investments in their country and other countries too.

What may go unnoticed by the casual observer is that the flag of Ghana supposedly carried by one of the masses seems to draw a line bet- ween the academician and the hand holding the fly-whisk, obviously representing culture and tradition on the one hand and the miner and the army officer on the other. This shows how the structure of authority in the Establishment is supposed to be. The miner, definitely representing the working population looks prominent with its enlarged bust.

Although there is a look of confidence on his face, the tilt of his head to make room for the army officer shows that he is not in control of his own destiny. The army officer, attemp- ting to keep a low profile cannot help being slightly ahead of the miner, emphasising where the "buck stays".

The academician, ideally represented by a woman, is desperately making attempts to move away from the shadows of obscurity, making sure that if she is not in the limelight she is visible enough to await a better tomorrow, a characteristic typical of the professional bodies in Ghana.

The hand clutching the fly whisk seems to be confident of one thing, a firm hold, for once there is a people, there surely will be customs and traditions, and institutions like chieftaincy can never be abolished, for if the masses are proud of the prominence given to the miner in the citadel of power, even though they know and acknowledge that the scholastic method of disputation the academicians put forward will finally be the accepted formation of the nation, culture is a social idea and they the people are the inventors, the creators, the geniuses.

The masses on the other hand seem to say that the country is full of citizens eager to push on with their attempts to find a just way of distributing the national cake, be it food, shelter or cash, if given the right implements, for they believe the fight is for the con- quest and defence of the liberty of the individual, for the federal principle, for the right to unite and to act, and not for the submission of the in- dividual, the annihilation of the free contract and the uniting of men into universal slaves for those in power.

But the implements given them seem to urge them to become models of heroism and humanity in the fight of barbarism.

On the front side, just below the inscription 'Bank of Ghana' and cutting across the star, a symbol Ghana is well known for, is the epigraph 'Freedom or Death'. Anyone familiar with the history of Ghana will notice that the epigraph does not sound well to the ears. 'Freedom' is not unknown in Ghanaian epigraphs but the ending had always been 'Justice' and not 'Death'.

By freedom, it is meant that every Ghanaian is assured of his personal liberty and that he cannot be treated as a slave. He must be genuinely compensated for his efforts, and that he cannot be denied any civil liberties, liberty of action, power of self-determination, boldness of conception, freedom of movement, and participation in the privileges of being Ghanaian. The second part of the epigraph, 'Death', shows the extent to which the people must go to protect this freedom. There is therefore the need for every Ghanaian to protect his freedom even to the point of death.

The twenty cedi note spells nothing but revolution. A revolution begins with the rallying of the kindred spirits and is carried to completion by their united strength. And here it makes it no offence for the normally gentle and quiet Ghanaian to exceed the established limits of decorum and sociability.

Ghanaians always feel the need to involve themselves in politics, for despite the diverse ethnic groups, customary laws did much to create respectable authorities than did the power of matchets, spears and guns, and so to them, freedom is first and foremost a say in government and not a dominant minority with total concen- tration of power (the first mutual assurance for domination) who make decrees or laws, execute these decrees and carry out judicial decisions too.

Although there is a look of confidence on his face, the tilt of his head to make room for the army officer shows that the miner is not in control of his own destiny. The army officer, attempting to keep a low profile cannot help being slightly ahead of the miner

When such is the condition in a country, the dominant minority or 'The Establishment' gradually accumulate for their families the riches of the time, and the seeds for such petty ascendancy are already there and are increasingly manifesting themselves.

The masses will eventually wake up to the fact that there has been an ero- sion of their freedom, and that the authority as has been built up in the villages, towns, cities, statals and parastatals is in a tentative and groping manner.

They will rebel and struggle to oppose the Establishment with the implements given them, for they will know that there is no need to die defending an ideal but rather the essence of a revolution. Some of the people will perish in such a struggle but they will be honoured like Queenmother Yaa Asantewa.

And so the vicious circle of the twenty cedi note will go on and on, with internal conflicts, domestic struggles, street riots, bitter wars waged against those in authority and the reprisals that will follow.

Consolation is taken though from the inscription "Gye Nyame" or "Except God", thus placing our faith to overcome such a nightmare in the hands of God, which is symbolically represented by a hand knocking off (seemingly) the epigraph 'Freedom or Death', in other words, admitting that there could be no end to the "vicious circle of the Ghanaian Greenback" by the neglect of wisdom or the abuse of human ingenuity.

The symbols of identification on the twenty cedi note represent the symbol of change in Ghana now, but a symbol of a change must be meaningful. People do not only learn to understand by reading, but also by observing well a concise symbol and integrating its meaning when they fully understand it. Symbols with meaning, and I mean significant meaning speak for them- selves. They may not be attractive pic- torially, unlike the 'Ghanaian Green- back', but may enjoy a constant gaze due to the message they carry across.