Comment

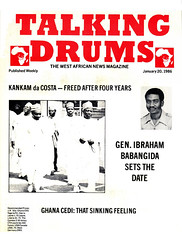

Babangida Sets A Date

In the public mind he acquired the reputation of the brave soldier during the abortive coup in which Gen. Murtala Mohammed was assassinated and inspite of having been linked with all coups since then, has managed to retain the soldier image rather than the 'armed businessman' image that many of his colleagues have acquired.

It might very well be that the announcement of a specific date for the return to constitutional rule would turn out to be the most astute political move yet to have been made by President Babangida. By one fell swoop, he must have put a stop to all potential critics on both sides of the Nigerian society - military and civilian. Apart from the sycophantic few who would tell anybody in power to stay forever, there is broad agreement that it is better for the country to be governed constitutionally.

By announcing a date, prospective coup makers must now find it that much more difficult to convince the public that they are performing a 'patriotic duty' by moving against the present administration.

The Gowon example must not have been lost on the present actors, for, by setting a specific date for the return to constitutional rule after the end of the civil war, General Gowon managed to secure a period of peace and stability for himself and the country. He only became vulnerable when he reneged on the original timetable.

The setting of the date would doubtless be useful to Gen. Babangida himself through the discipline that is necessarily imposed on the administration by having to work within a specific time span. They would know that they do not have a lifetime to play around with and whatever point they seek to prove will have to be accomplished within the time span.

In the public mind also it will be easier to accept the image that the military government seeks to portray of being a corrective regime that has been forced to take action to save the nation. It might very well be that one of the fatal decisions made by Gen. Buhari was his adamant refusal to contemplate setting a date for a re- turn to constitutional rule. Such a stand gave the impression that the soldiers were, in fact, only interested in power.

But more important, it should serve to dull the effects of any public disaffection. Politicians and aspiring politicians all now have a date towards which they can work and it would be that much more difficult for anybody to work up public anger against President Babangida.

There will be some disagreement, of course, over whether October 1990 is too far in the future or too short, but it might be considered by all that there is not that much difference between three or four years or five years.

President Babangida has given himself about as much time as the constitution would have given if he had been elected by the people and that should be ample time to make his presence felt for good or for ill in the country.

We note that he has been quick to point out that the ban on politics is still in force. Undoubtedly, he wants some peace and quiet to be able to assert himself. It is perhaps worth considering that part of the reason for the instability of civilian governments in West Africa lies in the fact that there never seems to be enough time for the political parties to organise properly. The time between the lifting of the ban on politics and elections is usually far too short for any long lasting alliances to be made.

Everybody is usually in such a rush that dubious alliances, shotgun weddings and mergers without sound foundations are made just to beat deadlines imposed by the outgoing military regimes. The result is that people fall back to tribal allegiances to form and register parties and the possible emergence of genuine nationwide parties is that much more difficult.

Very often also, people complain that it is only the same old tired faces that emerge to lead the parties. But then with the limited time that is allowed there is never enough time for any new personality to prove himself in the arena before any elections.

It is probably worth recalling here that during the last elections in Ghana, the fielding of a 'new face' by the People's National Party helped it win the election but then the last votes had hardly been cast before people started having grave doubts about the suitability of the elected leader and ex-President Limann had great difficulty in performing his duties because he never had the full backing of his party.

It will not help anybody if President Babangida waited until January 1990 before lifting the ban on politics and then expect to usher in a new civilian government on October 1 the same year. The committee that has just been inaugurated to collate views from the public on the political future of the country will doubtless come up with a lot of interesting and useful recommendations. But they will remain beautiful words on paper unless they are given a chance to be worked out and the person in the remotest village feels part of the system that emerges. We would consider a period of two years as a minimum re- quirement in which President Babangida should allow for political parties to operate before the elections in 1990.

Having said all that, there is, of course, the more fundamental question surrounding the entire concept of 'handing over power' to a civilian government by a military regime and the unease that must now arise from the realisation that if something is somebody's to give, that person can always seize it back...for the moment though, everybody seems to be more interested in adjusting their minds towards October 1990. There is obviously a lot of excitement ahead.