WAI, indiscipline and the military

By Linus C. Okere

The search for viable political systems is the responsibility of both the army and the civilians. The military is a profession that is by nature violent, prone to rash decisions and dangerous adventures. The destiny of African people cannot be entrusted to those whose code of conduct is in the form of commands and decreesOne of the features of the ousted Buhari regime in Nigeria was its highly publicised War Against Indiscipline (WAI) The WAI campaigns were, however, based on a purely military thinking, ie. the application of force. The emphasis on force during the WAI phase explains why Nigerians quickly went back to the old days when General Babangida took over. It is commendable that the present administration accepts that force is not the best method of infusing discipline and now talks of voluntary discipline.

Before proceeding further, it is important to stress that there had been a similar concern about the level of indiscipline in Nigerian society during the Obasanjo regime, 1976-79. What the government did was to send army personnel into secondary schools. What this approach achieved was that soldiers spent most of their time serving as gatemen, and generally mis- behaving with the students.

These concerns have raised questions too about indiscipline in the army - the frequency to subvert the constitution in the name of rooting out corrupt and inefficient civilian governments. One is perhaps tempted to ponder about the above question, especially if we consider the scale of military intervention in politics. Some of these coups are necessitated by genuine concern for society's well-being, while some are organised by victims of very confused and confusing concepts, while still others are carried out by ambitious elements in the army.

However, should the army remain on the sidelines and allow a state of economic robbery and brutality to continue in the name of upholding democratic systems? Certainly not.

For a clear analysis, the criteria should be based on the concept of justifiable acts of indiscipline. This approach aims to defend military actions effected for the purpose of removing irresponsible, repressive and corrupt administrations. But to qualify for this category the coup plotters will have to avoid the application of the policies pursued by the team they removed, and indicate their commitment to democracy and the search for a more stable political system.

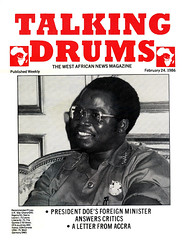

It is in the above context that we examine some of the recent coups in the continent. From the beginning, any serious observer would have known that the coup of Samuel Doe of Liberia was one of the bloodiest in recent memory. His domestic policies have been very repressive and he crowned his excesses by organising sham elections. None of these actions justified his 1980 takeover, so that the recent abortive attempt to remove him can best be described as a justifiable act of indiscipline.

A similar attitude can be employed in assessing Buhari's coup in Nigeria. The constitution had been abused and politicians blatantly disregarded the will of the people. Although it can be argued that corruption had existed since the inception of the military, this was controlled and protected by the means of force possessed by the army. What the civilians did was to proliferate the system through party specials, party campaigns, party friends and party heavy madams.

However, should the army remain on the sidelines and allow a state of economic robbery and brutality to continue in the name of upholding democratic systems? Certainly not.

Consequently, when the takeover came it was met with jubilation, but it was not long before Buhari and his friends showed their true colours. The government launched an attack against all the forces of democracy - the press, students, doctors, the legal profession and the academics which provided the atmosphere for the coup. The Buhari regime instead of practising policies that transacted tribal loyalties, rather pursued actions that only fanned the embers of tribalism. The policies were discriminatory against southerners, southern politicians were humiliated, and generally detained politicians were made to wear prison uniforms and were treated as if they had already been found guilty.

It became clear too that a section in the army was motivated by jealousy and openly resented the dynamism of such southern politicians as Lateef Jakande and Jim Nwobodo. Despite the ideals of WAI, slogans such as patriotism and nationalism were designed to ensure the security of the skeletons in the cupboards of some army officers. Therefore, the policies of the Buhari regime denied it in the legitimacy of classifying the 1983 takeover as a justifiable act of indiscipline. His regime did not declare its commitment to a constitutional government.

There are other instances in Ghana, Ethiopia, Uganda, Togo and Benin. What they all prove is that the celebrations and excitements which normally greet military coups are premature. All takeovers should be treated with a degree of scepticism until the plotters reveal their true intentions. And where such intentions betray the public, the people must rise up against such governments.

The search for viable political systems is the responsibility of both the army and the civilians. The military is a profession that is by nature violent, prone to rash decisions and dangerous adventures. The destiny of African people cannot be entrusted to those whose code of conduct is in the form of commands and decrees. The fact that the civil service exists during a military government, and there are civilians as political advisers, commissioners and economic advisers, shows that they cannot be administrators. The job of the army is to guarantee the security of their nation and not to be rulers. No amount of certificates, diplomas and degrees can alter the mentality of those in the army. It is a mentality that prides itself on being recklessly forceful. It is contrary to the concept of choice and constructive criticism.

Civilians cannot go on being romantic about the niceties of democracy if they themselves are not prepared to uphold such values. Political interference in the affairs of state governments by the Shagari administration is one example of abuse of democracy. Those movements for democracy should teach their members how to be responsible and responsive to the plights of their citizens.

The only political education the army needs is to be reminded that their coups and suspension of the constitution can only be accepted as justifiable acts of indiscipline if they declare a genuine commitment to a return to constitutional government and the restoration of fundamental human rights.

'Whispering Drums' returns next week