Whispering Drums With Maigani

by Musa Ibrahim

Political Debate vs The Military

"The prevalence of military coups in many African countries including Nigeria made the 49 'wise men' who framed Nigeria's 1979 constitution to assert thereof that it is unconstitutional, and hence illegal, for the military to take-over through a coup d'etat, the instrumentalities of government from the elected representatives of the people. The making of such a provision or the real force behind the clause could only be seen as a basically moral force in that it points to the fact that a military coup is bad or morally undesirable, something that ought not to occur no matter what. But the unanswered question is: who, for example, is supposed to enforce the constitutional provision once the civil authority has been overthrown, knowing that the real coercive power which underpins the authority of the civil regime is the military? Perhaps the provision was deliberately meant to be exhortatory, a call on the people to rise against the military in defence of the constitutional order …”Two years and two months ago today, following the 31st December 1983 military coup d'etat that toppled the democratically elected civilian government of former President Shehu Shagari, an indignant Kenyan journalist, in his assessment of the entire Nigerian political situation made the following remarks: "The Nigerians seem to us to form their governments the way children build card- houses; no sooner started than completed, and no sooner completed than blown away, and no sooner blown away than re- placed, and no sooner replaced than forgotten."

With just a Silver Jubilee to its credit, the end is not yet nigh for Nigeria. In fact, for those who subscribe to the whimsical belief that life begins at seventy, at only twenty-five years old, Nigeria has grown faster than her shoes. And with oil as the main engine of the country's economic growth, there have certainly been profound changes in the country's economic fortunes to the extent that Nigeria today is a growing concern internationally.

All would have been well except for the sad fact that on the political front, Nigeria has not come out with a lasting and viable political culture or institution that will guarantee the much needed political stab- ility for its teeming population. Still operating on an ad-hoc basis, the political arrangement of the country has come to revolve around a vicious circle between the country's politicised armed forces and the hapless and often confused politicians, with the military dominating the scene because they monopolise the nation's instruments of coercion.

The Kenyan journalist's euphemistic remark on the Nigerian political scene gives an adequate picture of the politics and government in Nigeria since independence a politics and government that have witnessed one parliamentary system of government, one presidential system of government, six successful military coup d'etats with countless unsuccessful attempts and eight heads of state, in just only 25 years. To many observers within and outside of Nigeria, the country's present political arrangement is both dangerous and volatile, one that needs a complete overhaul. But the question that ultimately arises is: who is better placed to carry out this overhaul? Is it the military who have been the main destabiliser of the country's political system, or is it the politicians who invariably become helpless against the onslaught from the military because they have no arms?

On the two occasions that Nigerians have had a go at representative civilian governments, it has been the military that have wilfully terminated both experiments on the grounds of incompetence on the part of the politicians. Never at one time did they lay the blame on the system of government that was being operated. So, with the benefit of hindsight, one can therefore assume that there was nothing wrong with both systems. Consider the Parliamentary government. inherited that system of government from its British colonial masters at independence, in a colourful and dignified ceremony.

The politicians undoubtedly had to have problems at the initial stages - after all, they were armed with a Constitution that was made in England. This notwithstanding, the Constitution, which was designed to give the country's three huge but mutually antagonistic ethnic groups breathing space and freedom but within the borders of a single country, was effectively being put to use.

October 1, 1979 saw Nigeria with a different political arrangement. The system of rule that was inaugurated on that memorable day was marked by two special and significant events: first, the coming into being of the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1979, and second, the installation of a popularly elected civilian as Executive President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. And unlike the Constitution of the First Republic, the 1979 Constitution was drafted by Nigerians and made for Nigerians and ratified or sanctioned by the Nigerian military. It reflected the country's past experiences and was capable of influencing the nature and orderly development of the politics of the people (this was put to test in the 1983 elections where it scored a pass mark). Yet the Nigerian military had the system overthrown.

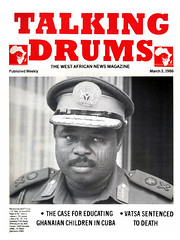

President Ibrahim Babangida is genuine in his desire to hand-over the reins of power to the politicians in 1990. To demonstrate this commitment, a 17-man political bureau was inaugurated by the President to gather, collate and evaluate the contributions of Nigerians to the search for a viable political future. And three weeks ago, in a radio and television broadcast to the nation, the Chairman of the Bureau, Prof. Samuel Cookey listed 28 major items for discussion by Nigerians. Among the 28 items was the role of the armed forces in Nigerian politics. This is a very interesting point indeed, because, genuine as Babangida's commitment is to march the soldiers back to the barracks, the "Old Man" cannot guarantee a coup-free Nigeria after 1990. And this is where the chairman of the political bureau has to come in.

Rather than allow the debate to be hijacked by the press, the political debate must start with the Nigerian military. The military must be asked to suggest for Nigeria the system of government that they can guarantee will withstand military intervention. The military must be asked to suggest the system of government that will allow the collective will of the people to enjoy the unquestionable respect, support and loyalty of all sectors of the country, be they uniformed men or civilians.

The military must be asked to tell the Nigeria nation why they often feel it is their moral right to destabilise the country whenever they feel like it. Answers to these questions must be answered because the usual excuse of intervention by the military to stop corruption is no longer convincing since history has shown that no military regime in the world has ever escaped charges of corruption. This is the task before Professor Samuel Cookey and his men.