The military-servants or masters? 3 by Col. Annor Odjidja

Colonel Annor Odjidja

Col. Annor Odjidja, former Director of Military Intelligence in the Ghana Armed Forces concludes this thought-provoking three part article on the Armed Forces' intervention in politics with Ghana as the main reference point. (Part 1, Part 2)The tendency for our men in uniform to intervene might have been contained, if they had been kept busy. One of the simplest ways by which this could be achieved was all the-year- round training. The Ghana Armed Forces however did not train. There were reasons for this. Lack of equip- ment made training impossible. Train- ing funds were usually diverted for other tasks. Thirdly, since 1966, all our leaders had been suspicious of military training exercises. Plans for such exercises were almost always suspend- ed for one reason or another. The result was that troops did not have any- thing to do. They were bored by daily routine. Idle minds breed discontent. They therefore had to find something to expand their energies on. Thus the recourse to coups!

The opportunity for intervention is also created by the concentration of units in Accra. Fifty per cent of our armed forces are located here. The rally and assembly of troops for a coup is easy to undertake. Detection of such conspiracies is made more difficult by the concentration of soldiers in the large cantonments of Burma Camp.

The concentration of government in Accra provides a good opportunity for the coupmaker. The infrastructure of government is within easy reach from Burma Camp. Identification of strategic and sensitive targets is easy. Thus a determined attack or neutralisation of these objectives can bring the government down.

In planning his intervention, the coupmaker always considers the likely reaction of the government in power. If he anticipates resistance would be fierce, he will abandon his enterprise. The real fact, however, is that there is an appreciable lack of political and military will to resist coups in Ghana. The coupmaker only has to make a move and all forms of resistance collapse within a day. Our soldiers are most reluctant to fight under such circumstances. There are reasons for this attitude. The first is that they are not ready to die for their country and operate on the principle that if they surrender early, they are likely to suffer, at the worst, detention for sometime and then be released. In their perception the fight is with the civilian, not the soldier. It is amazing how soldier solidarity on such occasions works to ease the coupmaker into power.

There has been a popular misconcep- tion in Ghana that coupmakers are disciplined and patriotic, and have a high sense of selfless devotion to duty. They are not and it is time that this idea is buried. The profile of the coupmaker is that he is a disgruntled officer who is very dissatisfied at his lack of prospects for promotion and higher appointment; whether this is due to his own misconduct is not a consideration that enters his head. His personal disaffection provides him with the opportunity to blame authority for his problem and he therefore takes steps to remove the source of the problem.

He is usually the subject of a service enquiry into an aspect of his profess- ional life. Here, it is important to note that his coup action has almost always coincided either when a decision is about to be taken upon the conclusions of the enquiry or midway through the enquiry. He is usually in financial difficulties. It does seem to be the case that his financial problems provide him with the strong motivation to seize power. The coffers of the state provide ample sources of rich pickings. If not there are many avenues for wiping out accumulated debts or his impecunious state.

Is it any wonder then that after his installation in office, the regime becomes identified with corruption and scandal, sometimes of a far more serious nature than the ones he uses to justify the removal of the politician? The blame for the rise of the coup-maker should be laid firmly at the door of our armed forces. There are systems within the armed forces for identifying and disciplining bad officers but there seems to be unwillingness or reluctance to use the system to clean out such officers from the armed forces. Decline in professional standards and the apathy of the commanders of our armed forces are the reasons why the systems do not work.

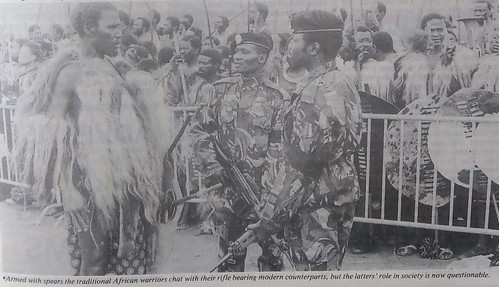

It is always argued by those in favour of military intervention in our politics that our men in uniform possess skills and qualities that make for efficiency and rapid development; that the soldiers can wipe out corruption and that because the armed forces is national in outlook, it can promote a sense of national identity; that by their knowledge of security, they can promote stability. They can do none of the above.

The Ghana Armed Forces is not efficient in the use of its own resources and can therefore make no claims for efficiency. There are worse cases of corruption within the Ghana Armed Forces than the coup protagonists ever realise. Stability cannot be maintained where personal jealousies have a way of transforming themselves into attempts to remove the military government. Hence the numerous counter coups. It must be pointed out that the divisions which a military seizure of power engenders among soldiers have a way of translating into tribal, economic and social conflicts and disagreements. The country eventually mirrors these divisions.

Our men in uniform have actually stopped the growth and maturity of our national civil institutions. They have retarded orderly national devel opment. In the process they have destroyed the armed forces. If you look at it carefully, you will find that our men in uniform leave the country with fer more problems than they found it, whenever they are forced to handover. Their lack of understanding of the political process and insensitivity to political factors force them to make serious mistakes that have a fundamental impact on the political, social and economic structure of our society. Once they intervene, our men in two functions: to train to fight and to govern. There is an old Mediterranean proverb which says that a good thief cannot be a good policeman. This is at the core of the failure of our men in uniform in their role as governors.

Are coups then preventable? To find the solution to this problem, it is essential that we understand what happens when a coup occurs. The conspiracy to overthrow a government succeeds because there is usually a plan of action. It consists of moving troops simultaneously at a command to seize key and sensitive points in the area where the government operates. Usually it is the capital of the country.

The assumption is that once these objectives are under firm control, the government falls. A coup depends for its success on strategic paralysis. This means that the surprise, shock and the speed of action that the coup opera- tions introduce into the defined opera- tional area induces a sense of paralysis in the government and prevents it from taking steps to foil the coup.

PROPAGANDA

The first six hours of any coup action is critical for its leaders, because plans have a way of going wrong. The plan may be leaked and the govern- ment may prepare counter-action. Alternatively, the government may summon enough loyal troops to foil the coup. This period is therefore the time when they are most vulnerable. Hence their determination during this period to eliminate or neutralise key members of the government and their first intention to seize the national radio and television. This media provide a useful propaganda tool for showing that they are in control.In Ghana the capture of the radio and television station signals to all troops outside the capital that the coup action has been successful. Nobody wants to be left out and soon soldiers start to jump on the bandwagon. The coup is a success. But is it?

This scenario does not always work out this way. In Kenya in 1982, the dissident air men seized the radio and counter-action. announced a take-over but there were sections of the Kenya Armed Forces prepared to resist and they fought their way into the radio station and crushed the coup within hours.

There are three options available to any government for dealing with military intervention. The first is the use of all available internal resources to defeat the insurrection. The first plank in any counter-strategy is the use of troops. It must be noted that coups are usually organised by a small group of soldiers who hope that surprise and speed of action in taking over strategic points and neutralising key members of the government can guarantee them success.

The task for the government is to move forces immediately to nip the and do not go to work. attempt in the bud. The more time passes without any counter-action, the greater the likelihood that the coup-makers will gain an advantage. Strategic paralysis will set in. Counter-action must take place within the first six hours. It has a greater chance of suc- cess. Action against a coup presuppos- es that troops are loyal. The coup-maker usually makes sure he has 'sleepers' in loyal units who would take action to frustrate any counter-action. They usually do this by seizing control of the unit through the arrest or elimination of key officers and men in loyal units. The solution to this is to identify and neutralise 'these sleepers' before they do any damage. Nobody likes to be on the losing side. Perceptions of success are usually what guarantee success of coups.

A second plank in the strategy is the mobilisation of the population against coups, by rioting, demonstrations etc. It is difficult to get this done in Ghana because people are afraid of dying and they tend to be anti-govern ment anyway, whoever is in power. They tend to justify their inaction by making excuses and showing a general reluctance to heed to principle. A reason for this attitude may be that public confidence in civil institutions is weak. If mobilisation is efficiently organised, it can neutralise the efforts of the coupmaker within his critical hours.

Consider what will happen to coups if

a. Public servants refuse to co-operate

b. Workers go on strike and neutralise anything that enables the coupmakers to function.

C. Somehow radio and TV refuse to function even if efforts are made to correct the malfunction.

d. Public utilities cannot operate for sometime, particularly in the barracks.

e. The intelligence and security forces refuse to cooperate and cease to function and go underground.

Any of the above options can be used singly or in combination for resistance against coups. Whatever be the case if the planks in the counter action strategy are planned and implemented with skill, coups can be preventable, whether in Ghana or elsewhere.

The consequence will be that the military usurpation will collapse. But the rush to welcome the coup, the reluctance of the population to oppose the coup, the reluctance and unwillingness of troops to oppose the coup, the fear of what the soldiers will do, the divisions within the civilian population and the eagerness with which sections of the elite rush to the coupmakers to offer advice and help. These are the reasons why a small group of soldiers succeed in imposing their will on the population. By the time people realise that they have been conned, it is too late.

The second option is the use of external forces to crush a coup attempt. This involves the use of foreign troops. The agreement of a foreign country to assist will usually be contained in a defence pact, ratified by both parties - the home and foreign governments. The government agreeing to support the threatened government must have the means and resources to fly in troops quickly to nip the attempt in the bud. The assisting government(s) must have a strategic interest or stake in the country threatened before they will agree to sign the pact of assistance and undertake the enterprise. If not, the agreements can be regarded as only worth the paper they are signed on.

The Senegalese intervention in Gambia was possible because of Senegalese interest in the Gambia. For intervention by the assisting government to occur, the political will to do so must exist. Otherwise political considerations must combine to prevent the dispatch of troops. The hand of the assisting country will be strengthened if the internal resistance to the coup is of such a scale as to provide a useful causus belli and the government under threat is seen to be in some control somewhat. No country is prepared to let its troops die for a country whose citizens are seen not to be prepared to die for themselves.

There is a third option. This is the creation and use of special elitist forces within the country under threat of a coup. Usually these forces are under the direct control of the Head of Government and can be deployed once a coup occurs. There are however problems. The first is that special forces always tend to invite opposition from the regular standing army.

The second is how to retain the loyalty of such forces that they will prove loyal in an emergency. Coupmakers will try to subvert these forces to prevent their entry into the fight against the coup or to persuade them to join forces with them. These problems are not insurmountable but the use of special forces requires careful planning and special measures.

At the end of this examination of the nature of our armed forces, the question we should ask ourselves now is: What are the Ghana Armed Forces for? This is pertinent because it seems to me that there is confusion in the minds of our men in uniform as to their defined roles in Ghana. For a country that has serious economic problems, it is the height of naiveté for us to continue to expect that a large share of our limited resources should be allocated to our defence needs. This allocation will make sense if current order. threats to the nation are of such a nature as to justify the expenditure. CONCLUSION It is estimated that between 7 ½ % and 10% of our GNP goes to maintain our armed forces. By all the known criteria of measurement, this is too high. This estimate underlies the mis- application of Ghana's scarce resources, given the fact that there are no clear roles to match the current size of our Armed Forces.

To find an answer to the question posed above requires an analysis of who constitute our enemies. The enquiry assumes that as a nation, we must have enemies. But what sort of enemies? We have accepted that our neighbours cannot be our enemies and even if they are, they do not have the means and resources for offensive action against Ghana. In assessing the external threats from this source of elsewhere, we have to find out whether the potential threat that we face cannot be diffused by diplomatic or political action. Do we have the means to fight, if we were to go to war?

We have accepted that our ability to go to war must be conditioned by the resources that we have. Firstly, they are limited, and we have serious economic problems. The matrix of choices that we have in dealing with current threats leaves us with options which need not be military. The conclusion of our examination of the possible external threats leaves us with two choices: a violent and non-violent response. Since we concede that we cannot possibly adopt a violent response by ourselves, we either have to accept the non-vio lent response (i.e. diplomatic action etc.) or seek the support of a friendly government to provide us with an external security umbrella. But against whom? Since we cannot see any real external threats to us, a policy of putting a high priority on the diplomatic means and a low priority on defence to meet the threats must be found.

Having accepted that we run no risks if we use diplomatic and political action to diffuse any external threat, then the only use we may have for our armed forces will have to be threats of internal peace such as terrorism, riots, sabotage, serious breakdown of law and order etc. In accepting these as the most likely operations scenarios, we have to ask ourselves whether the police cannot deal with some of these threats. If we hand over responsibility for handling low-level internal conflicts to the Police, then our armed forces can be limited to containing the most serious breakdown of law and order.

If that is so, then there is no justification for maintaining the present size of our armed forces. A cost/benefit analysis of our armed forces indicates that we have more men under arms than we really need. We now have to relate the size of our armed forces to its employment. Only then can we hope to be spared the cost of maintaining an expensive toy.

I do not see Ghana having anything larger than a force of 1,000 men. To continue to maintain the present level of around 15,000 men is wasteful in resources and serves no useful military need, unless of course we think of our men in uniform as helping to reduce unemployment in Ghana. In that case, we may as well turn it into a Workers Brigade and employ more than we have now, say 200,000?

There are many white elephants we acquired after independence. One of them surely must be a large armed force. It is time we recognised that we do not need this. Ghana is a small country and it is time we adjusted our inflated perceptions of our importance to one which accepted reality. Why not better start with our armed forces?